How a 19th‑century fertilizer law let an American whaler plant a flag that still carries a seat in American Samoa’s legislature, even though no one lives on the island.

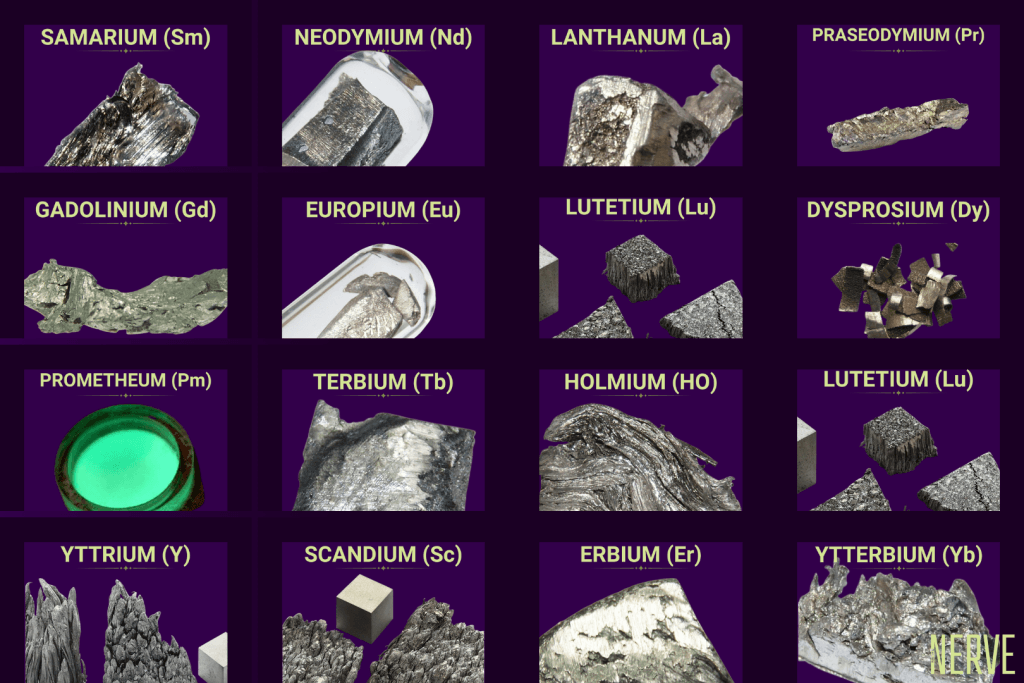

In 1856, Congress passed the Guano Island Act, thereby authorizing any citizen of the United States to take possession of unclaimed Islands containing deposits of guano (bird and bat excrement, contemporaneously prized for its use as a fertilizer and as a gunpowder precursor), and to report the possession to the president who could then determine whether to treat it as appertaining to the United States.

Roughly 100 islands have been claimed in this manner with the last attempt at doing so as recent at 1997.

The law extended US criminal jurisdiction to such claims and allowed the federal government to protect them with force. It was a legal invitation to American adventurism.

Eli Hutchinson Jennings

Eli Hutchinson Jennings, a whaler from Long Island, New York, arrived on Swains Island on 13 October 1856 with his Samoan wife, Malia of Upolu. Before landing, he purchased title from a British Captain Turnbull, who said he owned the island by right of discovery. One account gives the price as 15 shillings per acre and a bottle of gin.

That’s about $89/acre after adjusting for inflation.

Jennings proceeded to set up a copra operation (a term for the dried white meat of a coconut destined for oil extraction) as a private plantation under the auspices of the US flag.

There’s no evidence that guano was ever mined there, but in 1860, the United States Guano Company filed a claim to Swains under the Guano Islands Act, thereby shielding Jenning’s property from absorption by another nation.

Official annexation

In 1909 the resident commissioner of the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands tried to assess an $85 tax on Swains copra profits and implied United Kingdom authority. The American flag had been reported flying over Swains decades earlier. Jennings protested, and in 1911 the British government refunded the money and conceded that Swains was an American possession. The question of formal status lingered until 1925. On 4 March 1925 the island was joined administratively to American Samoa.

On 13 May 1925, Lieutenant Commander Campbell Dallas Edgar of the United States Navy raised the flag over Swains from the USS Ontario. About 100 people lived there at the time. The Navy established a radio station in 1938. During World War II the atoll supported a weather and plane‑spotting post and had a population of about 125.

An island in decline

On 2 December 1980 the United States and New Zealand signed the Treaty of Tokehega at Atafu. The treaty delimited the maritime boundary between Tokelau and American Samoa, and it entered into force on 3 September 1983 after ratifications were exchanged at Pago Pago. New Zealand confirmed U.S. sovereignty over Swains Island while the United States relinquished its historic claims to the three Tokelau atolls. Tokelau later referenced Olohega, the Tokelauan name for Swains, in a draft constitution preamble as an historic island, yet New Zealand and the United States have treated sovereignty as settled since the treaty.

Representation without residents

The 1960 American Samoan constitution guaranteed Swains a delegate in the House of Representatives of the Fono, which is American Samoa’s bicameral legislature. For decades the Swains delegate held privileges on the floor and full committee rights, yet no floor vote. In a referendum on 8 November 2022, voters approved an amendment that granted the Swains delegate a vote in the House. On 16 January 2025 the U.S. Department of the Interior approved the amendments. Implementation stirred a brief fight in the territorial government in February 2025, but the legal change is now in force. Because the island has no residents, the delegate is chosen by former inhabitants and by descendants of Swains families. Since 2004 the seat has been held by Suʻa Alexander Eli Jennings, a descendant of the original Jennings proprietors.