Americans need to set standard that defines when, if ever, a family of foreign descent is fully vested with the American identity and granted the ordinary standing, trust, and respect that comes with it.

Conservatives are hotly debating what it means to be an American, whether such a thing as a “Heritage American” exists, and what it takes to become a real American. Some of the most extreme proponents suggest that only the political opinions of Heritage Americans should matter, while others equally extreme suggest anyone in the global population of 8 billion can become an American of equal stature, overnight, so long as they follow the proper legal procedures.

Neither of these positions are adequate or politically feasible. On the one hand, an improperly defined and exclusive definition of Heritage American will render the political movement marginalized at the ballot box. On the other hand, a propositional nation of foreigners holding copies of the Constitution would result in a nation unrecognizable in character and governance.

What is a Heritage American?

The most restrictive say only those who can trace ancestry to a family that arrived before the Civil War may claim the title. Others have suggested that arrivals from as recent as the first part of the Ellis Island Era could be considered as having ownership of America’s heritage.

A more useful alternative to Heritage American

American conservatives desperately need to have a separate conversation about entry into the American identity writ large. And they need to be realistic. The United States can, potentially, deport millions of illegal immigrants and perhaps even denaturalize some here legally as well. What we cannot do is remove all the millions who did arrive through legal avenues and childish tantrums in response to this reality serve no purpose.

So any discussion of the re-emergence or delineation of an American identity would do well to not wholly and forevermore reject the future progeny of those who are not culturally American despite obtaining citizenship.

The Gold Standard of American identity:

With this in mind, a clear gold standard for American identity emerges: Americans with four American grandparents are culturally distinct from Americans from immigrant-origin households.

These are individuals who have a family history that is tied to this nation and its people and who have been fully steeped in its culture as a consequence. Today, it might mean that you have stories of your grandfather landing on the beaches of Normandy or surviving the Great Depression.

Whatever lay at the foundation of one’s story of America, it simply cannot be one of instant gratification as is being searched for by our most recent waves of ungrateful immigrants.

American ethnogenesis, not palingenesis, is necessary:

Ethnogenesis is the formation and development of a novel ethnic group. In practice, its the process by which a population comes to recognize itself (and be recognized) as distinct from its peers. It’s not a magical genetic event so much as it is a cohesive and coherent development of a shared identity.

Palingenesis is the renewal or restoration of a people, ethnic group, or race. In political theory, it’s best understood as the myth of “national rebirth.”

If the golden standard of American identity is adhered to alongside a restrictive immigration system, the development and cementing of a final American identity can be achieved though it would take multiple generations to do so.

Why an immigrant and those born to immigrants will never be fully American:

An immigrant may never be fully American, but their descendants may be able to.

Is an American child raised by two Mexican immigrants a cultural match with a child raised by two American parents?

Is the child of black Americans the same as the child of two African immigrants? Do the children have the same understanding of the civil rights movement?

It’s nice to think we live on magic soil and that neither nature nor nurture has any say in the outcome of a child’s life, but most people understand life to be more complicated.

True American experience:

A people are a culture’s custodians and it is only through a long, multi-generational process of enculturation that newcomers are able to matriculate into the society as fully integrated and assimilated.

To be a fully respected steward of the common American destiny, one must be fully steeped in the culture. In other words, they have to be sufficiently American.

An immigrant, or even the child of an immigrant who has spent their entire life in the United States, cannot truly claim part of the same shared experience or hold an intimate understanding of this country or its culture in the manner of one who was born to parents who, were themselves, born to parents who were raised in the United States.

This is the true essence of being fully American: something transformative happens in the American household over the span of generations.

Americans are called not only to preserve the republic but also, as necessary, to hone and utilize the tools afforded to us in order to achieve our shared prosperity.

How can those who have only just arrived or those raised by those raised elsewhere have a mind and soul properly tuned for such a project?

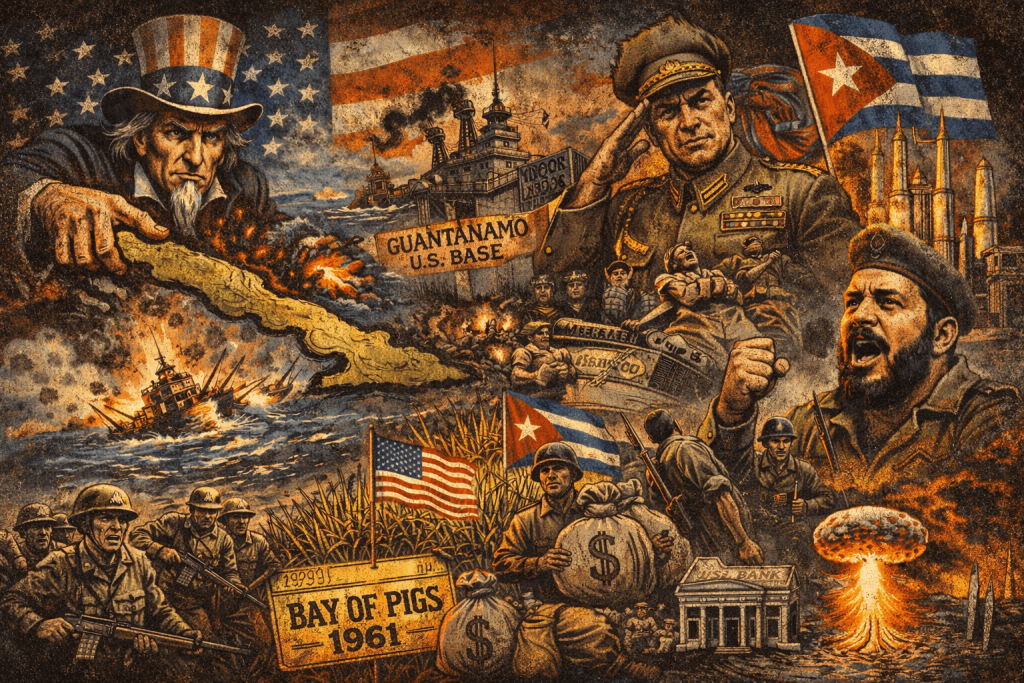

The Founding Fathers vs the Subcontinent:

The Founding Fathers, including George Washington and John Jay, understood that, even in the American infancy, this land would become more than just a creedal weigh station for the misbegotten and downtrodden to usurp those naturally born.

In Federalist Paper 2, John Jay celebrated the unified culture of the American people:

With equal pleasure I have as often taken notice, that Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country, to one united people, a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established their general Liberty and Independence.

Skin in the game:

It would be remiss to write on this subject and leave hanging the question of what we are to do with this formulation of American identity. It would be equally remiss to ignore what group of immigrants is so ardently arguing in favor of America as a propositional nation.

That argument comes largely from Indians, Somalis, and other extremely recent arrivals attempting to carve out space in the United States. These are immigrant groups who, by and large, have no point of reference in the broader American story to latch onto. Of every race, creed, and ethnicity

Mexicans and other Spanish speakers can claim some aspect of the Southwest and the conflicts therein. Asians worked the rails of the first transcontinental railroad, meeting Irishmen from the other side. Many Japanese Americans can trace their ancestry to the late 1800s. Black people were brought here as chattel.

Almost every ethnic group, no matter how annoying their whining may be, has a far more legitimate voice than these newcomers who cannot speak of any shared history. Indians largely started arriving here in numbers in the 1980s and Somalis only in the 1990s. They have not sacrificed. Their grandfathers weren’t in the Greatest Generation, their fathers weren’t pressed into service for Vietnam.

They came here on visas and reaped a bounty they didn’t sow, then demand thanks for enriching the native-born population while telling them what it means to truly be American. It’s the height of insult and pretension.

So what should the American people do with this framing?

They should become demanding of the immigrant and the immigrant, for his part, should develop a creed of their own, one of sacrifice. This is the core of American ethnogenesis, meaning the slow formation of a people through shared experience, obligation, and loss, not merely shared paperwork.

A workable social standard is simple: Americans with four American grandparents are fully vested, meaning granted the ordinary standing, trust, and respect that comes with being “of” the people without qualification. Before that point, a family is still in formation, still proving itself, still living inside a kind of probationary history.

It was through blood, sweat, and the ultimate sacrifice that true American families were enculturated into our society, meaning fully absorbed into its norms and obligations. It was a costly and hard-fought endeavor. The least an immigrant and his children can do is respect that sacrifice with one of their own: remain on the sidelines of the identity-defining political arguments and entrust their fate to the Americans who had already built and stewarded the society they arrived in. Let their descendants pursue civic engagement, and do not soil their opportunities by creating needless cultural friction.