The United States has not conducted a nuclear explosive test since 1992, and no permanent member of the United Nations Security Council has conducted one since 1996, while several states, including the United States and Russia, continue non-explosive subcritical experiments under a continuing moratorium.

President Donald Trump said the United States would resume nuclear weapons testing, asserting that Russia and China are conducting testing programs and that the Pentagon should match them on an “equal basis,” a claim he posted shortly before meeting China’s President Xi Jinping in Busan, South Korea; his remarks reversed more than three decades of US restraint on nuclear explosive testing and framed the move as a response to rivals.

Open source records still show no verified nuclear explosive tests by those major powers in recent decades.

What we are counting as a nuclear test

A nuclear test, for the purpose of this post, is a nuclear explosive test in the form of a detonation that produces a self-sustaining fission or fusion chain reaction.

These would be tests banned by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) that prohibits such detonations in all environments, though the treaty has not entered into force.

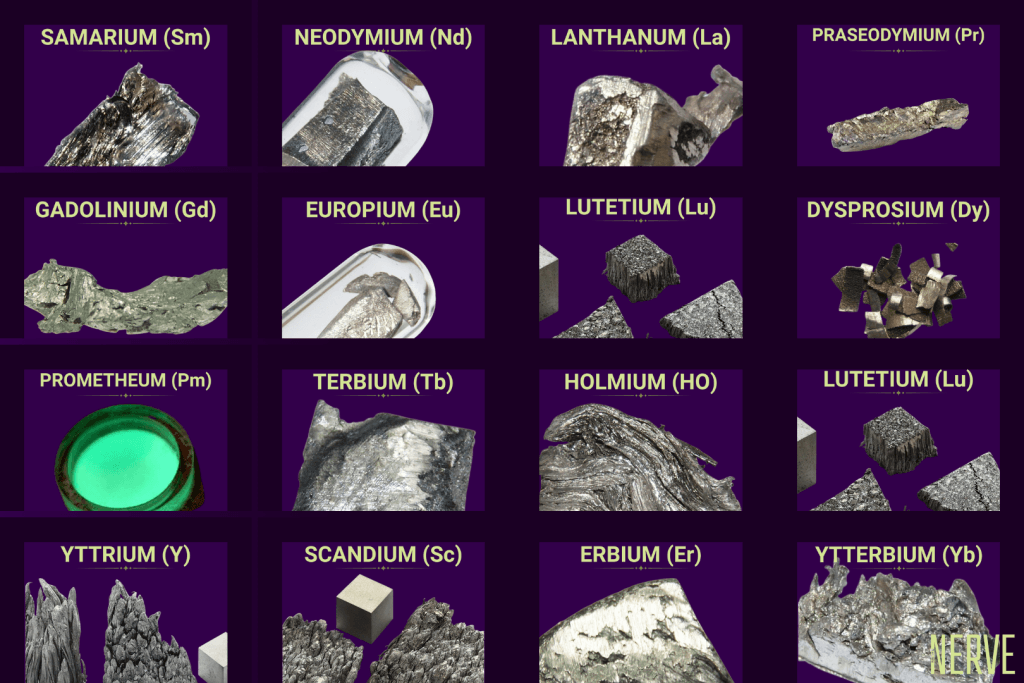

By contrast, subcritical experiments, which use small quantities of nuclear material under conditions that do not achieve criticality, produce no nuclear yield and are conducted to collect diagnostic data about stockpile performance.

Even something like the Poseidon torpedo-class delivery vehicle announced by Russia the other day does not qualify as a nuclear test, nor would a similar program or venture in the United States be considered as such.

Nor are tests like these what President Trump was referring to when he suggested that the United States will begin nuclear tests once again.

This really isn’t something world powers are actively engaged in:

Outside the major powers, North Korea conducted six underground nuclear explosive tests between 2006 and 2017, with the last occurring on September 3, 2017.

India and Pakistan each carried out nuclear explosive tests in 1998, then halted, and neither has publicly conducted a test since. Israel has never acknowledged a nuclear explosive test, and there is no confirmed open-source record of one. The five nuclear-weapon states under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT, the cornerstone arms control treaty that limits the spread of nuclear weapons) stopped nuclear explosive testing by the mid-1990s.

What the major powers are actually doing now

The United States ended full-scale explosive testing in September 1992 and has hence relied on Stockpile Stewardship, which includes subcritical experiments at the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS, the primary U.S. underground test location), high-performance computing, and materials science.

On May 14, 2024, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA, the U.S. agency managing nuclear security) executed a subcritical experiment at the Principal Underground Laboratory for Subcritical Experimentation, part of a continuing series designed to sustain existing warheads without nuclear yield.

Russia revoked its ratification of the CTBT in late 2023 to align its legal posture with the United States, which signed but never ratified the treaty, yet Russian officials state Moscow would only resume explosive tests if Washington did so first.

Since news of the Trump administration’s intention to reinitiate nuclear testing, Kremlin spokesman Dmitri S. Peskov reiterated this position.

China has significantly modernized infrastructure at its Lop Nur site, increasing readiness, but there is no public, verifiable evidence of a Chinese nuclear explosive test. It is unclear whether China will conduct a test of its own in response to any American detonation.

Verification reality and the monitoring record

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO, the Vienna-based body that oversees the global monitoring network) operates the International Monitoring System, a worldwide array of seismic, infrasound, hydroacoustic and radionuclide stations, that detected all six North Korean nuclear tests in near real time.

This network, supplemented by national technical means such as satellites and regional seismic arrays, makes the clandestine conduct of an underground nuclear explosive test by a major power unlikely to go unnoticed.

Enhancements to site infrastructure, such as tunnel refurbishment or new instrumentation, are often intended to support subcritical or hydrodynamic work. To date, there has been no CTBTO-confirmed detection of a nuclear explosive test by any permanent Security Council member since the 1990s.

Policy stakes of ambiguous rhetoric

Arguing that “others are testing” conflates subcritical experiments with nuclear explosive testing and risks eroding the political norm against yield-producing detonations.

Resuming explosive testing by any major power would undermine decades of restraint, likely trigger reciprocal actions, and complicate nonproliferation diplomacy just as modernization cycles accelerate. The legal status of the CTBT, which lacks entry into force, does not negate the de facto global moratorium observed by every major power, a norm reinforced by the ease of detection and the limited technical value of new explosive tests for states with mature arsenals. Policymaking that treats subcritical experiments as equivalent to explosive tests mischaracterizes current practice and compromises the clarity of public debate.